© 2017 WebRightServices.net

|

The bristling antennas, miles of wire and all the technicians are gone now, but the old Suddard Farm on Chopmist Hill in Scituate is still dotted with the ghostly reminders of one of World War II's best-kept and most important secrets.

For it was here on Chopmist Hill in March, 1941, that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) under Commissioner George E. Sterling, established and began operating a top-secret, radio-monitoring station. It was the largest in a nationwide network of 13 similar installations, and -- due to peculiarities of the terrain and certain atmospheric conditions -- it was the most effective. The station on Chopmist Hill could intercept distant radio signals with astonishing clarity, and in wartime, that was a critical advantage. While Rhode Island joined the nation in home-front sacrifice -- severe gasoline rationing, ersatz chocolate and horsemeat instead of beef, to name a few -- the band of 40 radio operator-technicians from the FCC's Radio Intelligence Division (RID)1 conducted a superb spy operation that directly affected the waging and final outcome of the war. Personnel in Scituate routinely monitored weather reports that were a key to troop movements and bombing missions in Europe. With uncanny frequency, the station intercepted the radio transmissions of German spies positioned in South America and North Africa. Chopmist's reception of North Africa was so good, in fact that the station had no difficulty picking up -- and turning to good use -- radio transmissions between the tanks that comprised the Desert Fox's infamous Africa Corps.  Electronics Illustrated, May 1969

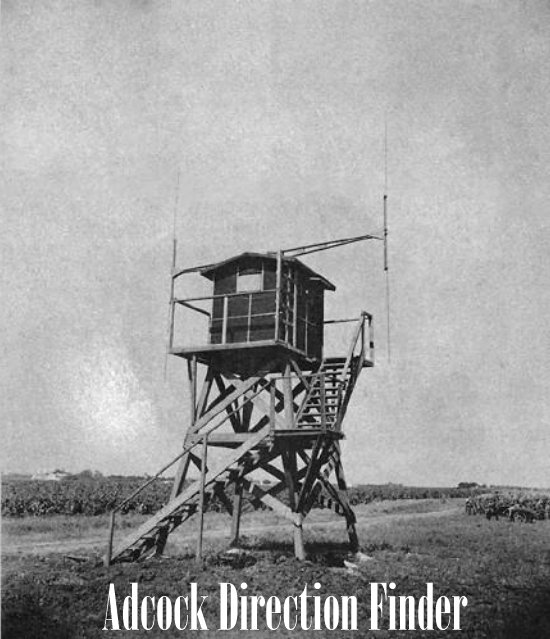

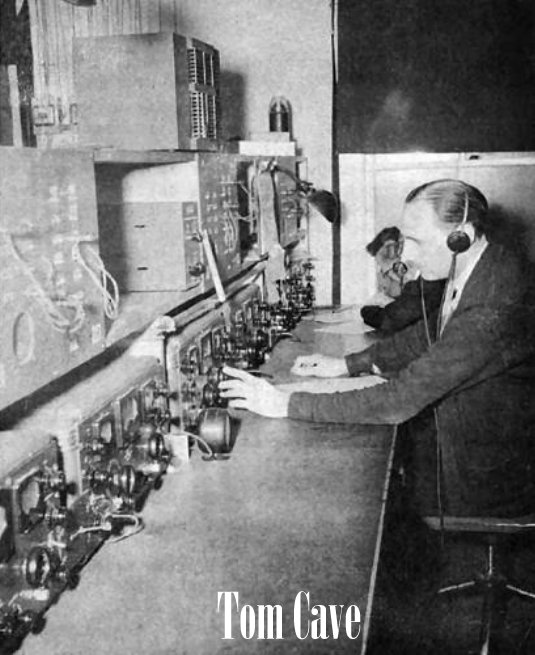

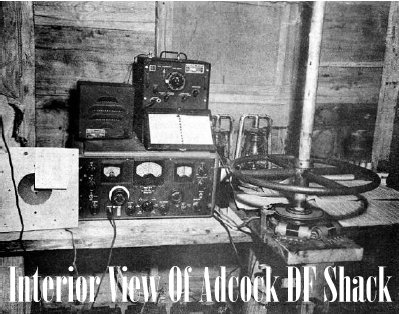

But to this day -- 40 years after Japan's devastating attack on Pearl Harbor and 36 years after the war ended -- few Rhode Islanders are aware of the spectacular battles fought on the little hill right in their own backyard. "C'mon, you're pullin' my leg" or "You gotta' be kidding" typify the responses of skeptics when told or asked about the illustrious history of the North Scituate farm. Originally, the station was set up in peacetime to police the airwaves for illegal radio transmissions and to assist in air-sea rescue operations. On one occasion, actress Kay Francis, en route home from a USO tour in Europe, was aboard a plane that was lost off the coast of Florida. No formal radio installation on the seaboard was able to pick up the pilot's signals, but the Chopmist Hill station did, and the monitors in Scituate directed the plane home safely. As the war intensified, so did the role of the Chopmist Hill station -- and the secrecy surrounding it. The installation became a virtual mini-city, complete with its own power-generating station in the concrete blockhouse. Nearby stood a wooden barracks building that housed the RID crew. Antennas were everywhere, anchored by guide (sic) wires attached to heavy metal plates cemented to the ground. The station itself was jam-packed with supersensitive radio receivers, transmitters and direction finders, and it was all so top-secret that not even the 40 technicians working there knew its purpose. Armed guards patrolled the area, and even visitors on official business could not approach the farm without a state police escort. Even the Narragansett Electric Company, which played a key role in establishing the Chopmist Hill station, didn't realize just what it was doing. Company crews were sent to the station with instructions not merely to install utility poles, but to sink them more deeply into the ground than normal, thereby ensuring that the tops of the poles would be below tree-top level and hidden from view outside the farm.  No sooner was the work completed than Thomas B. Cave, who supervised the facility for the RID, ordered all the poles moved to a different spot. No sooner was the work completed than Thomas B. Cave, who supervised the facility for the RID, ordered all the poles moved to a different spot.

"I thought we'd have a revolt on our hands in Scituate," said former commissioner Sterling. He is 87 now and lives in quiet retirement with his wife, Margaret, on an island in Maine's Casco Bay. "The folks at Narragansett (Electric Company) thought we were crazy. We called in their utility crews to dig holes and install a whole bunch of telephone poles. Next day, we called them back to move all the poles about two feet." Regardless of how much consternation and confusion the unexplained move may have caused, the relocated utility poles gave the station optimum radio reception. By the end of the war, the inconvenience was gladly forgiven anyway. When the role of the Chopmist Hill station was publically explained, a Narragansett Electric official said, "Hell, if I'd known what they were doing up there, I would gladly have dug holes all the way to Cairo!" But no one knew. Clandestine messages, encoded cryptographically, were being intercepted and copied verbatim by radio operators working 24 hours a day, who would then relay the messages to Washington, D.C., for deciphering. Commissioner Sterling said during a recent interview that he has never been able to figure out why the United States was caught napping at Pearl Harbor 40 years ago tomorrow. He said that for several months before the December 7, 1941, attack, the Scituate monitors were routinely intercepting Japanese messages that indicated military action was pending. RID supervisor Cave said that "Every three weeks, like clockwork, a Japanese submarine would surface in Tokyo Bay and broadcast to higher military headquarters the number of foreign ships that went in and out of the bay during the period" Cave recalls. The Scituate monitors helped thwart the Japanese attempts to bomb the United States with TNT-laden hot-air balloons. To keep track of the silent craft, the Japanese placed radio transmitters on aboard the deadly balloons. But the RID eavesdroppers heard the signals, related the information to Washington and U.S. fighter planes were promptly dispatched to destroy the balloons. In the entire course of the war, only a few balloons penetrated the electronic screen; one landed harmlessly in Wisconsin, and others drifted off into the Canadian wilderness. One of the most important jobs of the Scituate station was to intercept German weather reports from Central Europe. Broadcast in such a frequency that they could not be picked up in England, the signals bounced across the Atlantic Ocean to Chopmist Hill. the information played a vital part in British planning for bombing raids against Nazi Germany.  Most amazing was the stations ability to intercept virtually all radio transmissions sent by German spies in South America and North Africa. In fact, said Cave, who is now 79 and lives in Holmes Beach, Fla., Wilhelm Hoettl, one of Germany's foreign intelligence area chiefs, affirmed during his interrogation by the U.S. Third Army in June, 1945, that German intelligence had not been able to establish a single wireless connection, either in the United States or England. Most amazing was the stations ability to intercept virtually all radio transmissions sent by German spies in South America and North Africa. In fact, said Cave, who is now 79 and lives in Holmes Beach, Fla., Wilhelm Hoettl, one of Germany's foreign intelligence area chiefs, affirmed during his interrogation by the U.S. Third Army in June, 1945, that German intelligence had not been able to establish a single wireless connection, either in the United States or England.

It was the Chopmist Hill station that discovered installations of German transmitters on the West coast of Africa. Even the British, who had their own monitoring stations in the region, were totally unaware of the existence of the enemy stations. It wasn't long, said Cave, before the British, via Washington, were breathing down the necks of Scituate operators for more and more information. Little wonder. During the seesaw battles between British forces and General Erwin Rommel's infamous Africa Corps, the Chopmist Hill station frequently picked up coded messages containing battlefield strategy from the German military leader to his subordinate commanders. The information was relayed to the British, who under Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery defeated the legendary Desert Fox at El Alemein. "That's nothing," Cave said. "At one time, we saved the British liner Queen Mary, from being sunk with more than 10,000 Allied troops on board." The Queen Mary was docked in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil awaiting departure for Australia. German spies in South America learned the ship's sailing schedule and precise Southerly route down the Atlantic, around Cape Horn and across the Pacific Ocean. The information was radioed to Nazi forces in Africa, then relayed to German submarine wolf packs prowling the ocean. Orders went out to sink the pride of England's maritime fleet. "We intercepted the German transmissions, alerted the British, and they ordered the ship to change course," Cave said. "Who knows," he said with a chuckle, "maybe there's still a U-boat commander out there somewhere wondering where the hell the Queen Mary is." On another occasion, the British asked the RID operators in Scituate to determine the nationality of a remote transmitter near the Aleutian Islands. It turned out to be a Russian station and, therefore, was spared the annihilation which was planned for the suspected Japanese facility. Does it seem far-fetched? Is it asking too much to believe that a secret radio station up on Chopmist Hill in little old Rhode Island could have done so much so efficiently for so many? Early on, the U.S. Army was skeptical, too, Cave said, so Army officials challenged the RID operators on Chopmist Hill to prove themselves. RID supervisor Sterling picked up the gauntlet. He told Army brass that his operators could pin down the exact location of any station within 15 minutes from the time it began operating. So, the Army set up a phony station inside the Pentagon, without notifying the FCC, and began transmitting. Sure enough, the team on Chopmist Hill pinpointed and identified the source within seven minutes. Perhaps, like people, every place has its day in the sun, too. World War II was Chopmist Hill's. It could not be so again. "The problem with Scituate now is one of population growth," said Anthony M. Gates, a former Navy radioman now employed by the FCC as a program analyst in Washington. "There are a lot of new homes, buildings and factories in the area, all of which tend to produce extensive interference with radio signals," Gates said. "that was not the case during the '40's." After the war, the station site was used as headquarters for Rhode Island's office of Civil Preparedness. The agency moved to Providence in 1965. Today, the rusting steel door to the blockhouse groans in protest every time farm owner Frederick Leeder goes inside to get some hay for his small dairy herd. The barracks building is gone, and its cement-slab foundation now serves as a platform for Leeder's large woodpile. The small concrete blockhouse is there, guarded still by its six-foot, barbed-wire topped hurricane fence. And nearby, a few stubby telephone poles still stand in the pasture next to Darby Road, like dedicated sentries ready to carry messages that will never come. 2 A Thunderbolt Strikes in Scituate  June 17, 1943, was a beautiful day for flying. The sun was shining, and visibility was unlimited as a formation of four P-47 Thunderbolts cruised leisurely across the skies of Scituate. The planes were on a training flight that had left Hillsgrove Airport in Warwick. First Lieutenant A A Marston was leading the flight, followed by Lieutenants J T Brown, O J Foster and R W Powell. June 17, 1943, was a beautiful day for flying. The sun was shining, and visibility was unlimited as a formation of four P-47 Thunderbolts cruised leisurely across the skies of Scituate. The planes were on a training flight that had left Hillsgrove Airport in Warwick. First Lieutenant A A Marston was leading the flight, followed by Lieutenants J T Brown, O J Foster and R W Powell.Without warning, one of the pilots began to experience a problem with his airplane when the engine began to sputter and lose power. The pilot radioed the others to inform them of his predicament as he dropped out of formation. Suddenly realizing that the problem might be with the fuel flow to the engine, he switched to an auxiliary gas tank, by that time, the engine had stopped completely and wouldn't restart. He was too low to consider bailing out, and it was obvious that he was going to have to make an emergency landing. The young pilot scrambled out of the cockpit, relatively unhurt. Once it was apparent there was no danger of fire, he surveyed the damage and no doubt wondered where he was. The crash landing was witnessed by two volunteer airplane spotters manning an observation tower in North Scituate. They quickly notified authorities, and within minutes, army officials, the state police and two Red Cross ambulances were racing to the scene. The pilot had caused more of a commotion than he realized. An interesting footnote to this story concerns the immediate area in which the plane went down. Few people know today the old Studdard Farm on Darby Road was the site of one of the best-kept secrets of World War II. Its location was a geographical anomaly, where radio signals from all over the world could be received with perfect clarity. The work there focused on intercepting enemy radio signals. Those who worked there were credited with saving the Queen Mary from being sunk with ten thousand troops aboard and for stopping Japanese attempts to drop bombs on American soil using hot air balloons. Therefore, it is understandable that the crash of a military aircraft practically in the backyard of the top-secret installation created quite a stir. After the war, the farm was considered as a potential site of the headquarters of the newly formed United Nations before the present New York City cite was chosen. Due to its historical significance, attempts have been made to have the old farm placed on the National Register of Historic Places, but various reasons, has not been successful. 3

1 "RID History" 2 Journal-Bulletin, December 6, 1981, Staff writer Jim McDonald 3 "Forgotten Tales of Rhode Island" By Jim Ignasher |