|

On May 9th, 2004 The Providence Journal

Featured My Collection In Their Collection Corner Section

COLLECTION CORNER - Rhody-made radios

Denise J.R. Bass JOURNAL STAFF

PUBLICATION: Providence Journal (RI)

SECTION: Home

DATE: May 9, 2004

EDITION: All

Page: D-01

The classified ad in The Journal's 1989 Yankee Trader read, simply: OLD RADIOS. The seller was an elderly ham radio enthusiast from Lincoln, with a passion for radios that spanned decades. He placed the ad with intentions of selling his treasured sets to a kindred radio buff; someone he could trust to take care of them after he was gone.

At that time, in 1989, Len Arzoomanian, an electrical engineer, often answered classified ads in search of old radios for his collection. His collection was varied; Philco, RCA, Crosley -- whatever caught his eye. So he made the short drive from North Providence to Lincoln to see if the old radios were something he wanted.

What he found there sparked a new interest and fine-tuned the way he collected radios.

The old man brought Arzoomanian and another perspective radio buyer into a workshop room in his house, where his radio equipment was set up. Among the dozen radios in the room, Arzoomanian spotted one he liked right away. It was a boxy wooden radio with a large kite-shaped loop antenna.

He knew it was unusual, with the six small holes above the dials. The holes, about the size of a dime, were big enough to show the tubes inside. Below the dials was stamped, "The Outlet Co., Providence, RI."

The other guy, whom Arzoomanian sized up as a car salesman type, was interested in it, too.

They both listened and asked questions as the oldtimer talked about the rare 1920s Giblin Broadcast Receiver and its maker, Thomas P. Giblin.

The old collector spoke from memory of Giblin, the inventor from Pawtucket who patented the honeycomb coil and helped launch WJAR at the Outlet. While Arzoomanian found himself engrossed in the stories, the other guy was seeing dollar signs in the potential resale value of such a rare radio. He badgered the old man to sell it to him, but the old man insisted the radio wasn't for sale.

"Finally this guy left and as soon as he left, he [the old man] said, 'you wanna buy that'? I know you'll keep it,' " recalls Arzoomanian, now 46. "So I said 'yeah, I would,' and so I bought it."

After his two-hour visit, Arzoomanian left Lincoln with the Giblin set and antenna, a Magnavox horn, and a five-page newspaper article from 1924 featuring a schematic of the set's circuitry. Thirteen years later, Arzoomanian says, "It's my favorite set."

SINCE HE WAS a young boy, Arzoomanian liked the early 1930s Zenith console radio that his grandmother bought when his father was born. She had a furniture refinisher pickle it moss green to match her dining room set. All the knobs were emblazoned with a lightning bolt-shaped "Z" for Zenith. The radio was a fixture in their kitchen as he grew up, but when they moved to a new house, it stayed under moving blankets in the cellar. Arzoomanian always kept that radio in the back of his mind.

His love for that radio, electronics and history led him to collect radios. Soon after he started collecting, his father gave him the Zenith.

Arzoomanian had been collecting radios for six years before he bought the Giblin, but he was so inspired by the discovery of his native state's rich radio history that he decided to sell off those radios and start focusing on Rhode Island-made radios and radio parts.

He had some success at the New England Antique Radio Collectors club's quarterly meets in Nashua, N.H., but he bought most of his radios from other collectors and by placing ads in trade magazines. "Once your name gets out that you like R.I. stuff, people kinda find you, too," says Arzoomanian. "They've got to be marked -- visually show it's from R.I. and I'll buy it. "If it's something kinda boring looking and not marked at all, I won't take it."

When he wasn't searching for radios, Arzoomanian was in the Rhode Island Collection of the Providence Public Library, researching R.I. radio manufacturers. In addition to Giblin's company, Standard Radio & Electric, he discovered Polle Royal, Ford, Wecco and Dymac. He found tube manufacturers such as CeCo, Triad and Blackstone, as well as manufacturers of various radio-related parts such as Warren and MarCo.

Something from each of these companies is represented in Arzoomanian's collection.

Today his collection consists of 25 radio sets, including the Zenith and a few non-R.I. favorites remaining from his original collection. They are displayed on a floor-to-ceiling shelving unit in his dining room, with assorted speaker horns (not made in Rhode Island), and a curio cabinet filled with coils, tubes and other locally made radio parts.

Arzoomanian's collection has two types of radios: crystal sets and tube sets. With some work, any of them can still be played. The crystal sets are older, and run not with batteries or electricity, but on the power from the radio station itself. Radio stations are tuned in by dragging a piece of wire, called a cat whisker, along a small crystal enclosed in glass. With a long enough antenna or a close, strong signal, a crystal set will pick up sound. To the uninformed eye, the crystal sets are barely recognizable as a radio.

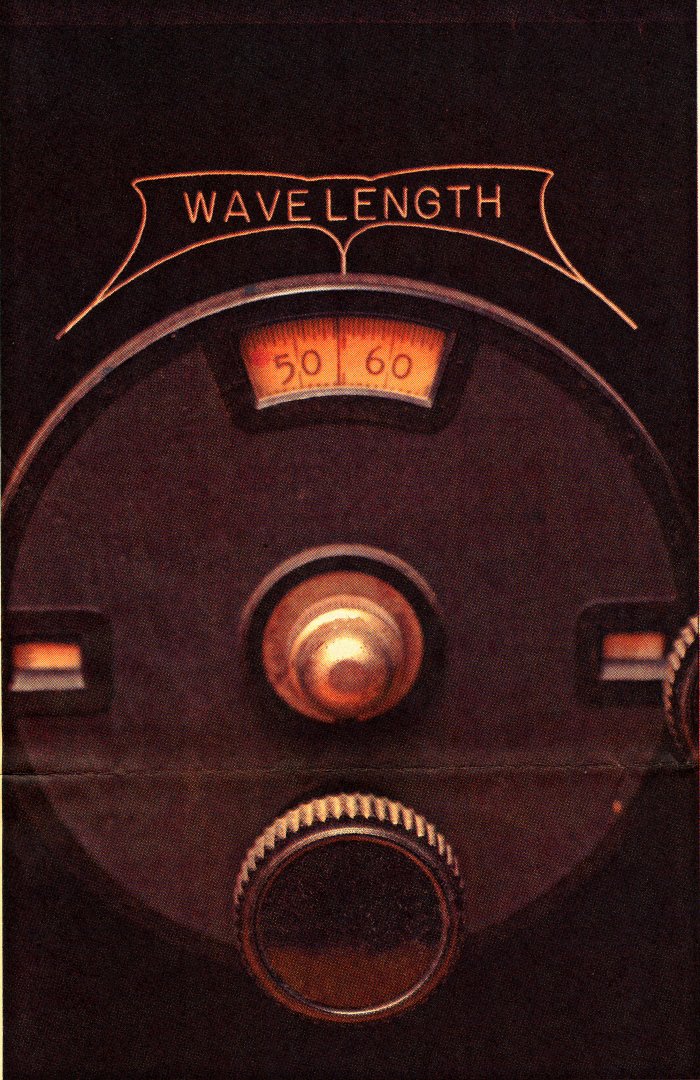

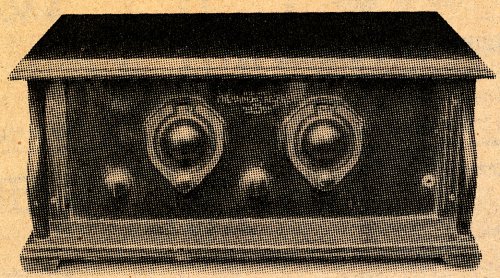

Tube sets, with their numbered dials and minimal scrollwork designs, are vaguely reminiscent of radios as we know them today. Although made by different companies, most of the tube sets in Arzoomanian's collection resemble each other. The number of dials varies from set to set, but generally, it takes three different dials to tune into one station on these old sets.

Many of the old sets came with a chart inside the cover where people could write in the numbers for each of the three dials for a particular station.

Larger than a breadbox, the rectangular wooden boxes are much heavier than they look. Hidden inside are three large batteries. "They were like car batteries," says Arzoo-manian. "They had acids in them. The acid would get on the furniture, burn holes in the carpet. It was nasty stuff. You can see acid marks on the wood on the back of some sets."

The batteries were unpopular, and some companies, such as the Providence company MarCo, developed battery-to-electric converters to replace the batteries. Arzoomanian built a "battery eliminator" from plans he found in a magazine. The device replaces batteries and allows the radio to run on electricity.

He tested it out by connecting a cassette player to a transmitter, and tuning the transmitter and an old radio to the same frequency. When he played the tape through the transmitter, a recording of old radio shows, the radio picked up the sound, and the old Polle Royal console came back to life. The sounds carried only a few hundred feet, but his friends were impressed. "When people look at the old radios, they want to hear something old come out of it," says Arzoomanian. "When you listen to it and you hear something new, its not so dramatic, I guess."

IN DECEMBER OF 1920, the world's first commercial radio station, KDKA, went on the air in Philadelphia. Soon after, the number of radio stations in America and the number of radios in homes grew rapidly. During this era, known as the "radio boom," maufacturers of radios and radio parts thrived and established a presence in Rhode Island.

It was a short-lived but productive time for the radio manufacturing industry in the state. In 1925, the Rhode Island Radio Fans Handbook, a 64-page directory of Rhode Island's radio industry, listed scores of manufacturers, retail stores, suppliers, radio stations, publications and schools. The technology changed rapidly, and most of the companies were unable to stay afloat in the explosive market.

ACCORDING TO Arzoo-manian, they were unable to survive RCA's invention of the super hetrodyne radio receiver in the late 1920s. The super hetrodyne featured smaller antennas and one-dial tuning, a welcome improvement over three-dial tuning. "It was so easy to dial the RCA set," says Arzoomanian. "They lent their patent to other companies, but the little guys just couldn't afford it, so they went out of business."

One might wonder how a collector keeps himself satisfied while collecting a topic as rare and finite as Arzoomanian's. But he is a collector who believes in limits. "I really have to watch myself. I can want to collect something really easily. You see something that's really cool and its like, I could start collecting it with out batting an eye."

When it comes to RI radios, Arzoomanian is happy to wait for that next rare find. "I get that feeling if I see a Rhode Island set," he says, "I just gotta have it." He is still looking for Giblin's three-piece tuner, detector and amplfier from around 1923. "I look all the time," he says.

"They're real hard to find," he says of the Rhode Island sets. "I probably haven't picked one up in about five years."

TRUE TO HIS WORD, Arzoomanian still has everything he got from the old man.

They kept in touch after that initial visit. "He came to my house and saw my radios," says Arzoomanian. "He loved the fact that his radio was there on display. I showed him some Rhode Island radios that he knew of but had never seen before."

Every so often the old man would send Arzoomanian a letter, but then the letters stopped coming.

His memory lives on in Arzoomanian's collection. Their story puts a twist on a familiar saying:

One man's treasure is another man's treasure.

by Denise J.R. Bass

* * *

Local claims to fame in radio history

Thomas P. Giblin established WJAR Radio at the Outlet Company with the Samuels Brothers, owners of the Outlet. WJAR went on the air on Sept. 6, 1922.

His obituary in the Pawtucket Times on February 18, 1963 claims that Giblin ''set up an experimental raido station in 1919, broadcasting phonograph music, and on this he based his claim to having been the state's first ''disc jockey." Giblin also held electrical and automotive patents, including one for the honeycomb coil, which improved inductance in early radios.

Gibson also played an important role in the first successful transatlantic flight in 1919. The article on the front page of the Providence Journal of Sept. 30, 1919, reads ''Improved winding on radio coils in the type SE-1405 amplifier used in the wireless apparatus of the ''Nancy" Four which Lieutenant Commander Albert C. Reed piloted in the first successful transatlantic flight, worked out by Thomas P. Giblin, a Providence radio engineer, was responsible for the high efficiency of the plane's receiving apparatus." The article explains that the method by which Mr. Giblin devised the amplifier was a closely guarded naval secret.

* * *

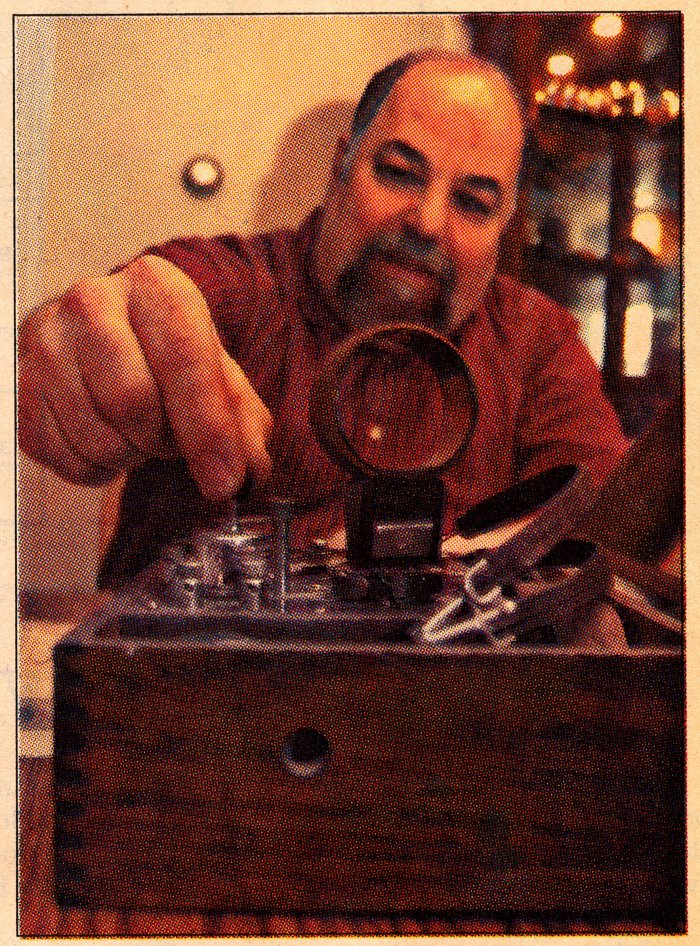

* Len Arzoomanian of North Providence demonstrates how to tune in a station on a 1920s Giblin Crystal radio.

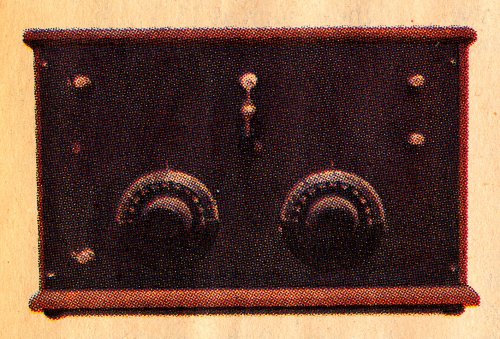

* The radio, left, that looks like a bank vault was made by the William E. Cheever Co., known as WECCO, of Edgewood.

* A wave length dial on a 1920s Supertone radio from Arzoomanian's collection. Supertones were from Bristol.

* A dial from a 1920s Dymac radio set in Arzoomanian's collection. Dymacs were made in Providence.

* Thomas P. Giblin, who helped start WJAR, made this 1920s tube amplifier radio set in Pawtucket.

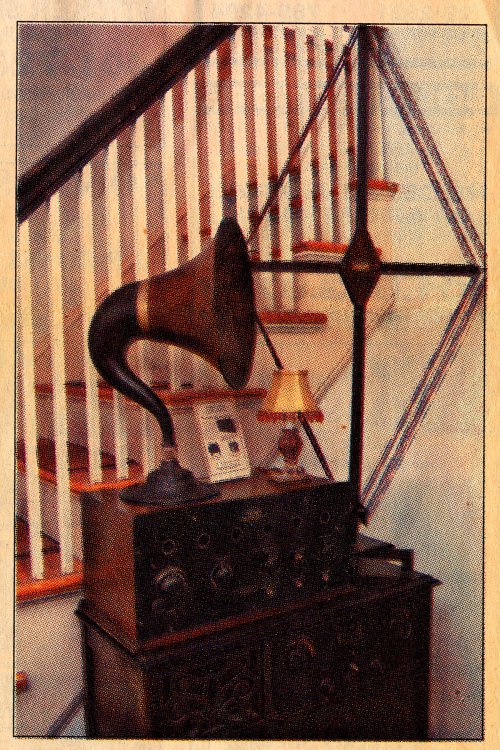

* The box with the kite antenna is a rare 1920s Giblin Broadcast Receiver, the radio that gave Arzoomanian his focus. It sits on a Polle Royal.

* Radios of the '20s required three dials to tune into a station. This is a Polle Royal.

* The Polle Royal radio company of Providence had many logos in the 1920s. Here, mer-maids sing into speaker horns.

* All these antique radio parts were made in Rhode Island.

* One wall of Len Arzoomanian's dining room is devoted to antique radios made in Rhode Island.

* An early Giblin radio from the 1920s, when the business in Pawtucket was the Standard Radio & Electric Co.

Journal photos / DENISE J.R. BASS

Letter from Charles Harrison's (Old man from Lincoln) Daughter

Dear Mr. Arzoomanian,

I read the article about you and your radio's with great interest. I believe the old man in Lincoln was my Dad, Charles Harrison., He told me the story about selling you the radio because he knew you would love it and keep it. He dearly loved his radio's and would have been so pleased to read this article. My dad passed away December 21st at 82 years of age. I am thrilled you still have the radio and the things you bought from him. No one else in the family was really that interested and I am so happy he changed your collection., He would be so happy to know the radio is cherished and cared for.

Sincerely,

Dale Pinocci his oldest daughter

|